By Jeff Kuhn

Because part of FLG’s consulting practice is to counsel corporate boards, we’re often asked about how a C-suite executive finds and secures a corporate board seat. The short answer is: “planning, persistence and patience.”

Identifying Board Opportunities: Network, Network, Network

In many respects the process of finding and being selected for a corporate board seat is similar to a standard job search, but it’s much harder and it probably will take much longer.

Like a job search, landing a board seat requires considerable networking to both identify opportunities and then stand out from the crowd and get yourself noticed. Fortunately, there are multiple platforms such as LinkedIn, with multiple active board discussion groups.

Your ultimate objective of participating in these groups is to demonstrate thought leadership and to become conversant with the issues that corporate directors at the company in question are discussing. Monitoring and engaging in these discussions will require a fair bit of your time as well as educating yourself about the specific issues at hand. My advice is to listen a great deal more than you speak, and identify those engaged in these conversations who seem have credibility, gravitas, and a reasonable following. Seed your board development network beginning with them. In the process, you will undoubtedly learn about additional resources to further your education about board leadership.

What About Using a Recruiter to Find Appropriate Board Options?

It’s certainly worthwhile becoming known by those recruiters who specialize in board searches (not all recruiters do), but just as with a job search keep in mind that you are not the client; you are the “product” being sold to the client. Also, you should be aware that the political ecosystem surrounding board searches is small and still a bit clubby. Interlocking board directorships can mean that an upcoming board vacancy will be filled only one or two degrees of separation from the originating board member’s professional circles.

Where to Learn About Being a Board Director

Being a director should be thought of as a profession by itself, and you need to learn as much as possible about how to be successful at it before you can break into the profession.

In my opinion the best education and board networking resources are found at the Stanford Directors’ College (SDC), offered annually by the Stanford Law School and now in its 26th year. When I attended SDC, I found the knowledge gained and the connections made to be first-rate. The admittance criteria are high at Stanford (and the cost is too) but assuming you qualify, you will find it very worthwhile attending this multiday session. Your employer or board may even be willing to reimburse you for the tuition. This year’s SDC is already sold out and is being held virtually.

You will also find a very good series of programs and credentialing offered by the National Association of Corporate Directors (NACD). NACD offers an Annual Directors’ Summit (online this year) attended by a couple of thousand directors, and NACD has local chapters throughout the U.S. These chapters meet regularly and are another great opportunity for networking and resource for board members and candidates.

All major accounting and law firms devote significant efforts and engage in a fair amount of content marketing to demonstrate their expertise to corporate boards. These include regular publications on a wide variety of topics including board compensation, best practices, diversity, ESG (environmental, social, and governance), cyber security, etc. There is a wealth of information to be had here, so plan on doing a lot of reading, and get on their e-newsletter lists.

Honing Your Board Expertise

A good way to differentiate yourself so that you become attractive to Board Development Committees and Chairs is to become an expert in specific fields relevant to specific problems that those boards are addressing. Public boards are required to have at least one financial expert, and that person serves as the Chair of the board’s Audit Committee. An obvious additional field is the whole subject of cybersecurity and cybercrime, about which we now seem to see daily headlines.

Which Board: Non-profit, Private or Public?

Non-Profit Boards

It’s easiest to begin your board career by serving on non-profit boards, which can be stepping-stones into the world of for-profit boards. NP boards govern enterprises ranging from the very small to the very large, so you should focus your search efforts on NP boards which have a majority of directors who have for-profit corporate backgrounds and careers, and ideally also sit on existing corporate boards. Such directors are familiar with proper board governance, the cadence of conducting meetings, and proper conduct. This can also be a good way to expand your professional network. Recognize, of course, that NP board service is rarely compensated.

Private Company Boards

Private boards worth spending time and resources on are generally backed by venture or private equity firms. I personally would avoid closely-held or family enterprises unless you are extremely aware of and comfortable with the company’s culture and governance authority. NOTE: The same, by the way, can apply to private-equity boards. I once served on such a board, where the PE firm owned over 95% of the company, and thus my role was effectively limited to rendering advice, not actually exercising any real voting authority.

VC-backed private companies generally don’t have independent directors until the company is within sight of its IPO and needs to have independent directors on the board prior to the S-1 filing. If you have a reasonably strong network of VCs, it is certainly worth networking inside this group, but be aware that the most important asset you would bring is your expertise in, or closely adjacent to, the industry of the company. When the company is still privately held, director compensation rarely includes cash, but often includes some equity. Once the company becomes public, director compensation always includes cash and equity.

Public Company Boards

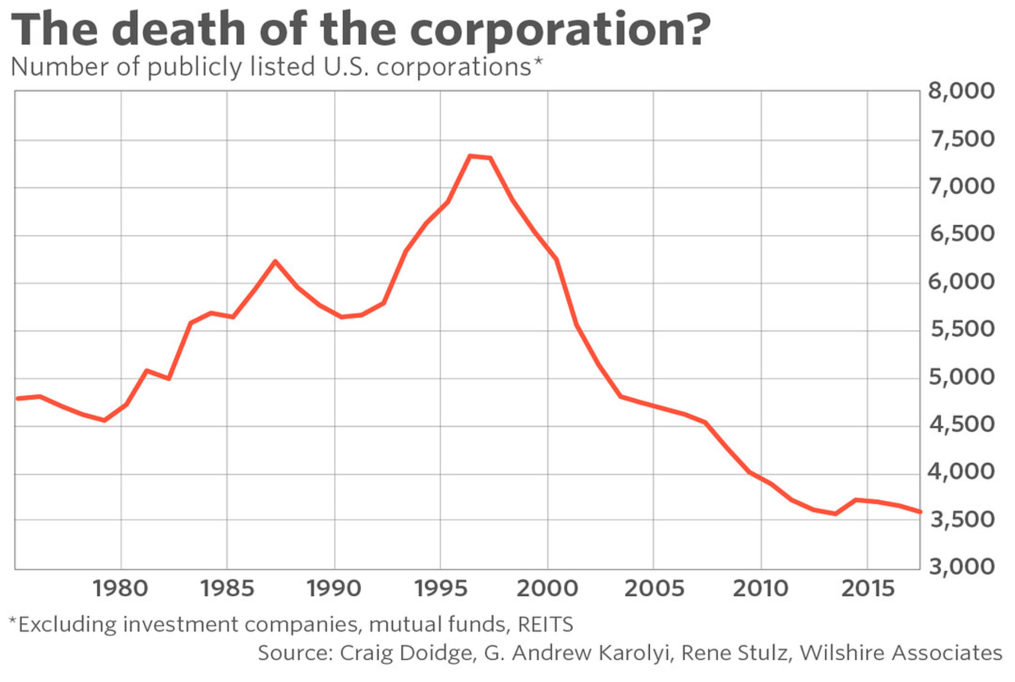

Getting selected for a public company board can be very difficult for at least two reasons: 1) there are many fewer of them than 25 years ago, and 2) unless you have personal “marquee” status (e.g., particularly valuable expertise), or help satisfy board diversity requirements, most public boards want experienced public company directors, not rookies.

The public corporate board universe is actually pretty small, and getting smaller. The chart below shows that the number of public companies has shrunk by about 50% in the last 25 years as a result of significant M&A and private equity buyout activity. Assuming an average of 10 directors per company, that’s only about 35,000 people in the U.S. If you further assume staggered 3-year terms, only about 12,000 directors come up for re-election every year, and actual director turnover is a very small fraction of that.

Board Membership: The Diversity Factor

Board Membership: The Diversity Factor

A monolithic perspective among a board’s directors is a recipe for poor decision-making and governance. Boards need to hear from and carefully consider broad viewpoints to generate sound decisions, especially since boards have begun to think of their fiduciaries more broadly than as just the company’s shareholders. Fiduciary responsibilities of boards is now often considered to include company employees, customers, and the communities in which they operate. This is also creating higher board director turnover as boards want to refresh the experience-base of their directors more frequently and are consequently shortening board tenures.

In September 2020, California enacted AB 979, which requires publicly-held California-headquartered companies to have at least one “diversity director” on their boards by the end of 2021, and up to at least three diversity directors, depending on board size, by the end of 2022. In addition, California’s SB 826 requires that, by December 31, 2021, all public companies listed on a major exchange and headquartered in California, no matter where they are incorporated, include at least two women on their boards if the corporation has five directors, and three women directors if the corporation has six or more directors. A minimum of one woman director is required if the board has four or fewer directors.

There are a variety of legal challenges to the California laws which are obviously far beyond the scope of this article, but significant momentum for such legislation promoting mandated board diversity is building within and among the SEC, NYSE, NASDAQ, and a variety of other U.S. states legislatures. It seems clear that a portion, probably a meaningful one, of the number of public director seats turning over each year will be reserved for diversity candidates.

Managing Director Risk

Corporate directors are fiduciaries, with consequences in terms of legal liability for their actions, or lack of actions. Companies indemnify their directors and secure Directors & Officers (D&O) insurance to protect their directors for the prudent discharge of their obligations, and corporate law (particularly in Delaware) can similarly shield directors from personal liability, but that doesn’t mean that the board and the company won’t get sued, a very expensive process.

The best first step in reducing your liability exposure as a director is to know the implications of your actions and how this impacts your liability exposure. There’s almost no such thing as too much education in this particular area, so be sure you are fluent in director best practices. If you’re being considered for a public company board, study every SEC filing of the company going back at least 3 years. For public and private companies, study your fellow directors’ backgrounds and what other board seats they may have. You want to make sure you’re surrounding yourself with competent, well-regarded professionals who have significant board experience.

The second step is to ask for a copy of the company’s D&O insurance policy. Make sure it’s large enough to satisfy any reasonable claim, and make sure it has so-called “A-B-C” coverage and a “Side A” policy.

Next, while interviewing for the board seat, speak to the company’s outside legal counsel and the company’s outside audit partner. Speak to each of the company’s C-suite officers. Ask the right questions, and make an assessment of what the board’s doing well and where it can improve. The company will conduct a background check on you before appointing you to their board, so it’s perfectly appropriate, and necessary, that you conduct your own due diligence on the company.

Lastly, come prepared to each board and committee meeting. A good rule of thumb is to allocate 2-3 hours of preparation for every hour of board and committee time. One thing all boards hate are surprises.

In summary, becoming an attractive director candidate means developing the skills, knowledge, and demeanor required of a corporate director, and then getting noticed. And that means study and networking. Best of luck on your board search!