By Eric Mersch

“Industry-Centric” SaaS business models offer an alternative SaaS company categorization to the “Customer-Centric” SaaS model, which is defined based on the “go-to-market” strategy used by a management team.

Both the Customer-Centric and Industry-Centric classifications provide valuable frameworks for evaluating SaaS companies. The successful SaaS CFO must understand both frameworks to support company decision-making, serve as a strategic business partner to the CEO and best portray the company’s performance to stakeholders.

I’ve written extensively about the Customer-Centric SaaS model, but in this article I’ll focus exclusively on the Industry-Centric SaaS model and its Horizontal and Vertical applications.

Industry-Centric SaaS Models: Overview

The Industry-Centric SaaS model divides companies into two classifications: Horizontal and Vertical. The Horizontal SaaS business makes software for use across all industries; the Vertical SaaS business makes software for a specific industry.

Horizontal SaaS companies were the first to debut because the market for basic administrative functions was broad, the R&D work was light, and the demand for cloud-based services was limited to basic functions. These are low barriers to entry and the Horizontal SaaS provider space quickly became crowded. Both new and existing SaaS companies moved into developing industry-specific software, giving rise to Vertical SaaS companies.

In this article, we will review the operational and financial characteristics of Horizontal and Vertical SaaS companies and demonstrate how vertical SaaS businesses achieve “riches in niches.”

Horizontal SaaS Companies

Horizontal SaaS companies develop and provide software for a specific function used by companies across all industries. When SaaS business models originated, the most successful venture-backed startups used a horizontal model. The reason behind this strategy was that it enabled the company to serve the largest possible market, i.e., the Total Addressable Market, or TAM. The software functionality only needed to be very basic, so the R&D resource requirements were typically light. The targeted functions to be replicated in the software – examples include customer relationship database management and bookkeeping – were well defined. These factors resonated well with the investment theses of venture capital firms.

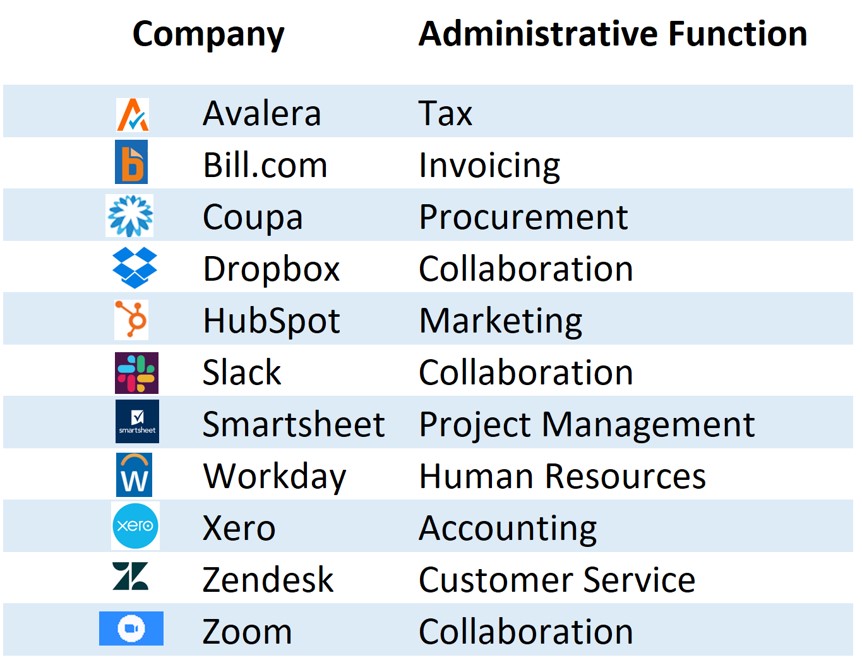

The most prominent example of Horizontal SaaS companies is Salesforce, which makes Customer Relationship Management software for use by direct and indirect sales teams regardless of the product or service the team is selling. Other high-profile examples are newer: the Microsoft Office365 productivity suite is the most widely used software in its category. HubSpot’s marketing software, with broad functionality, for inbound marketing, sales, and customer service is used by 86,000 companies in over 120 countries. Intuit’s products include the tax preparation application TurboTax, personal finance app Mint, the small business accounting program QuickBooks, the credit monitoring service Credit Karma, and email marketing platform Mailchimp. Avalara provides tax compliance solutions for direct and indirect taxes. Zoom, one of many office productivity applications, is in use by elementary schools, Fortune 500 customers and every size company in between. Current Horizontal SaaS companies that I used for public company comparables are shown in the graphic to the left.

HubSpot is considered a horizontal SaaS (Software as a Service) company because it offers a suite of marketing, sales, and customer service tools designed to serve various industries. Unlike vertical SaaS companies that tailor their solutions to the specific needs of a particular industry, horizontal SaaS providers like HubSpot develop versatile applications that address common business functions applicable across various sectors.

For instance, HubSpot’s platform includes features for inbound marketing, sales automation, and customer relationship management (CRM), which are essential functions for businesses in industries such as banking, telecommunications, retail, and more. This broad applicability allows HubSpot to cater to a diverse customer base, making it a quintessential example of a horizontal SaaS company.

By focusing on general business needs rather than industry-specific requirements, HubSpot can scale its services across multiple markets, providing standardized solutions that many businesses can adopt without extensive customization. This approach contrasts with vertical SaaS companies that develop specialized software tailored to a single industry’s unique processes and regulations.

HubSpot provides three primary offerings—a cloud-based platform for marketing (Marketing Hub), sales (Sales Hub), and customer services (Services Hub)—as well as a website hosting and management tool (CMS Hub) and a business process automation product (Operations Hub). The three main hub offerings have three pricing tiers: Starter, Professional, and Enterprise. The Sales Hub and Services Hub are priced per user; the Marketing Hub is priced based on the number of the customer’s marketing contacts.

Pricing is sophisticated enough to match company revenue to customer value add yet simple enough for potential customers to understand. You can also see HubSpot seeks to increase the average Annual Contract Value of its customer base with an Enterprise offering and additional product offerings. HubSpot has been successful with this strategy, increasing the average ACV above $10,000.

HubSpot offers a 10% discount for upfront payments to improve free cash flow. This pricing methodology is standard for Horizontal SaaS companies because customers are more price-sensitive. The company does not disclose the mix of monthly to upfront fees, but its free cash flow is positive and increased to double digits as a percentage of revenue for the most recent fiscal year.

HubSpot is an excellent comparable company for benchmarking purposes and for studying best practices. I have included the full financial profile below.

In summary, HubSpot’s designation as a horizontal SaaS company stems from its strategy to deliver flexible, scalable tools that meet the everyday operational needs of businesses across various industries.

Financial Profile of Horizontal SaaS Businesses

Horizontal SaaS companies have low Annual Contract Value (ACV) offerings because the product is so basic. Over time, as these companies grow their market power and software functionality, they are able to push up price points. But even today, large entrenched market players have low-cost offerings. Four of the large horizontal product offerings mentioned above (Salesforce, MS Office365, Hubspot, and QuickBooks) have ACVs that range from $90 to $480.

These low-cost SaaS options are very profitable because the cost to serve is extremely low and because basic, mature products require very little engineering support. Obviously, these players have built high value add products by increasing software functionality. High-end products command six- and seven-figure ACV pricing.

New Horizontal SaaS companies must continually compete with even lower-cost offerings hoping to capture market share and build their own high value products. Using a “Fast Follower” strategy, several of these companies have had considerable success. Online accounting software provider Xero, for example, was founded in 2006 and now trades publicly at a 22x Enterprise Value to TTM Revenue multiple. Contrast this success with that of Intuit, which launched desktop app QuickBooks in 1998 and its online version in 2004 (before Xero launched). Despite Intuit’s timing lead, Xero grew faster than Intuit’s Small Business Segment (products and subscriptions), outperforming the large competitor with an eight-year Compounded Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) of 52% versus 3% for Intuit.

By 2020, the horizontal SaaS space was fully matured and characterized by large competitors and commoditized offerings for every possible business and consumer function, leaving very few opportunities for new entrants. This high growth phase of Horizontal SaaS had passed and investors began moving to Vertical SaaS opportunities.

Key Takeaways

- Horizontal SaaS companies offer software for common business functions such as accounting, customer relationship management, marketing, and human resource management.

- This approach allows the company to serve the most significant potential market, the Total Addressable Market, or TAM.

- These software offerings have low Annual Contract Value (ACV) because the product is so essential. However, the business can still be profitable because research and development costs are low, end users need more support since many understand the administrative function, and the SaaS model makes software delivery efficient.

- Once the early Horizontal SaaS companies succeeded, new companies focused on writing software to support increasingly niche business functions such as online surveys and performance reviews.

- Because the software is so essential, the barriers to entry are low. This market dynamic allows new entrants to introduce competitive software using fewer resources to achieve the same revenue.

- Fast-followers are new entrants that catch up to and even overtake market leaders. The accounting software company Xero is a good example. It launched a low-cost product that helped drive a high-growth revenue trajectory. Xero nearly overtook market leader Intuit’s QuickBooks product within nine years.

- Salesforce, HubSpot, Microsoft 365, QuickBooks, and Zoom are examples of successful horizontal SaaS companies. Studying the path to success of these established companies will help you launch a new competitive product.

Vertical SaaS Companies

Vertical SaaS companies develop software that is tailored to a specific industry. Such companies evolved later than Horizontal SaaS companies; however, both the number of companies and their revenues are growing much faster. Today, we find numerous successful businesses, some of which are included in the chart below. The rise of Vertical SaaS led to the saying, “there are riches in niches.”

It’s easy to understand why Vertical SaaS companies developed more slowly than did Horizontal SaaS companies. With a very focused software application specific to each industry, these companies have a more limited Total Addressable Market opportunity. Software development is also much more resource intensive because digitizing specific industry functions is much more complex. Existing functions are customized to specific industry needs, are not well understood externally, and legacy systems tend to be older and more unique. All this make SaaS integrations more challenging. Many functions are subject to government regulations such as the health care privacy law, HIPAA. Some industries have entrenched, dominant market share competitors that may not be as open to new technologies such as SaaS. Even if the interest/openness is there, the software procurement experience might not be. Even with the evolution of Horizontal SaaS, these businesses played a key role in educating customers and in building skill sets internally, all of which took some time.

There was also an internal cultural issue that needed to be addressed before a Vertical SaaS solution could begin to take off. Success required industry experience, but this required collaboration between technology-minded entrepreneurs and industry experts. Early software entrepreneurs understood technology, but not the processes, procedures, and requirements of specific industries. Industry experts understood their businesses, but often didn’t have a technology mindset. These folks spent their careers learning the industry inside and out and this journeyman trajectory did not include experience with the latest in cloud technologies. Each competency had to move toward the other.

As the SaaS industry matured, these barriers fell away, opening the door to the rise of Vertical SaaS companies. Once they became established players, Vertical SaaS companies found that their business model had two main advantages: high sales efficiency and competitive advantage.

High Sales Efficiency

Vertical SaaS companies gain unique experience selling into industry verticals and typically employ a “Land and Expand” Go-To-Market strategy. These factors drive a higher overall sales efficiency than is found in Horizontal SaaS companies. A focus on vertical sales gives the software provider a detailed understanding of the optimum use case. R&D uses this information to tailor the product accordingly and this makes the sale easier. Customer case studies and customer references will help enable prospective customers to quickly grasp the value added and this, too, facilitates the sale. The Land and Expand strategy generates high sales efficiency following the initial contract because the cost to expand a customer is about half that to acquire a new customer. Plus, the payback period is materially shorter, estimated at 10% to 30% shorter by the Key Banc SaaS Survey.

Formidable Competitive Advantage

The complexity of SaaS software development combined with industry expertise creates a deep moat around their business for Vertical SaaS businesses. The stronger a company’s market position, the greater its pricing power. With reduced new entrant competitive threats, the incumbent Vertical SaaS player can raise prices to match the product’s value added. Experience in serving customers allows the company to provide consultative services, proactively helping existing customers navigate challenges that are well-documented and well-understood inside the Vertical SaaS organization. This further demonstrates value and, thus, supports the SaaS company’s pricing power.

Financial Profile of Vertical SaaS Businesses

Sales Efficiency is the key difference between Vertical and Horizontal SaaS businesses.

The Vertical SaaS business model sales efficiency can be seen in the data pulled from public filings via www.sec.gov. In the below charts, I plotted Sales and Marketing expense as a percentage of revenue for public Horizontal and Vertical SaaS companies for revenue tiers beginning at $25M and increasing by $25M increments through $300M. This approach normalizes the data to account for scale which shows what happens to sales efficiency as company revenues grow. The trendline is a logarithmic fit of the mean at each revenue tier. As an example, compare the two types of companies at $200M in revenue. The Vertical SaaS company spends $40M on Sales and Marketing; the Horizontal SaaS company spends nearly $60M.

The Vertical SaaS company set demonstrated metrics that would classify them as Enterprise, SMM and B2C SaaS business models. For example, the Average ARR for this set ranged from Dealertack at $5,000 to $10,000 at athenahealth to Instructure at $25,000 to Veeva Systems at ~500,000 to Opower at >$1.0M. The subscription to professional services revenue mix varied as described by the Customer-Centric business model classification. In 2013, Veeva Systems’ results showed a ~$550,000 Average ARR and a revenue mix of 56% to 43% for Subscription to Professional Services revenue, as expected for an Enterprise SaaS business model. In 2010, athenahealth results showed a ~10,500 Average ARR and a revenue mix weighted toward subscription at 97%. This is a typical result for a SMM SaaS business. Revenue retention also reflects the Customer-Centric model framework. The digital banking company Q2 uses an Enterprise SaaS Land and Expand Go-To-Market strategy for its installed customers and is successful at driving 120%+ net revenue retention. At the other end of the spectrum, Fleetmatics, with an $8,000 Average ARR, experiences net churn in the mid-single digits range.

Veeva Systems is classified as a vertical SaaS (Software as a Service) company because it develops cloud-based software solutions specifically for the life sciences industry. Unlike horizontal SaaS providers that create generalized applications for a wide array of sectors, vertical SaaS companies like Veeva focus on delivering specialized tools tailored to the unique requirements of a particular industry.

Founded in 2007, Veeva Systems offers a comprehensive suite of applications designed to address the distinct needs of life sciences organizations, including pharmaceutical and biotechnology companies. Their product offerings encompass customer relationship management (CRM), content management, and clinical trial management, all customized to comply with the stringent regulatory standards and complex workflows inherent in the life sciences sector.

This industry-specific focus enables Veeva to provide solutions that align with the operational and compliance demands of life sciences companies, setting it apart from horizontal SaaS providers that offer more generic software solutions. By concentrating exclusively on the life sciences industry, Veeva has established itself as a leading provider of cloud-based software for this sector, exemplifying the Vertical SaaS model.

Veeva Systems’ revenue growth trajectory is best-in-class for a Vertical SaaS company. It achieved a 41% Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) over the fiscal periods from 2010 to 2024.

The growth trajectory lags T2D3 because Veeva Systems used services to augment the software platform. 2010 revenue mix was 52% SaaS and 48% services. This revenue mix is typical among early-stage Vertical SaaS companies because the software is new and still requires a lot of technical and advisory support. Often, the company operates its software on behalf of the customer because the customer needs internal expertise. As the business progresses, the company continues to enhance the software by automating service features. Customers begin bringing the work inside and staffing teams to run the software. Thus, the revenue mix shifts over time. Veeva Systems achieved an 80% / 20% SaaS to services revenue mix by 2017 and has maintained it since.

Veeva Systems earned an 85% Gross Margin on its SaaS business in FY 2024. This rate is higher than the median benchmark of 78% and likely reflects pricing power since it is the market leader in this vertical. The services business has earned an average Gross Margin of about 20% over the past five years. This result is on the low end of the 20% to 40% we expect, but this low-end rate could imply that the company prices services revenue lower in exchange for a higher SaaS margin. Since SaaS is recurring, the increase in customer lifetime value likely more than offsets the lower service business margin.

You will notice how R&D expense grows as a percentage of revenue, even with the strong revenue growth over the past five years. S&M expense declines over the same time. We discussed how Vertical SaaS companies achieve higher sales efficiency above. The continued decline of S&M expense implies that the company’s status as a market leader requires a lower investment in S&M as a percentage of revenue.

Veeva Systems has continuously generated positive EBITDA and Free Cash Flow since fiscal year 2014, the first year these figures are available. This result is also consistent with Vertical SaaS company performance because the software adds more value to the vertical than does a Horizontal SaaS company to the broader economy.

The average customer ACV, shown here as “Average Subscription Revenue per Customer,” demonstrates that Veeva Systems is a genuine Enterprise SaaS company. The lesson is that the two classifications introduced in this book cannot be considered separately. Any given SaaS company will demonstrate characteristics of the two classifications.

Key Takeaways

- Vertical SaaS companies offer software that is tailored to a specific industry rather than a specific function.

- Vertical SaaS companies were typically founded after Horizontal SaaS companies because the software complexity is high and the target market is small.

- Many Vertical SaaS companies were founded by industry operators who recognized a niche opportunity and built productivity software to address the specific problem.

- Companies that operate a vertical strategy can achieve high sales efficiency because the use case is well-defined and the software built specifically for this purpose. The product itself drives the sales motion.

- Once established, Vertical SaaS companies’ experience in the industry serves as a formidable competitive advantage and this raises the barriers to entry.

- Vertical and Horizontal SaaS companies’ financial profiles differ in that the former has higher sales efficiency as measured by Sales and Marketing expense as a percentage of revenue and this frees up cash flow for investments in Research and Development or to improve cash flow.

- Veeva Systems serves as a good Vertical SaaS comparable company due to its high SaaS Gross Margin, its sales efficiency and profitability. And its history of moving toward a higher mix of SaaS to services revenue is common to that of many Vertical SaaS companies.

Summary

Both the Customer-Centric and Industry-Centric classifications provide valuable frameworks for evaluating SaaS companies. The CFO’s role is to provide operational and financial insight to the management teams and to translate business performance into reporting for investors. Therefore, the CFO must understand both frameworks to succeed as a SaaS CFO.

Other SaaS articles by Eric Mersch: